Walking the dog; we chat to Paul Swanson about learning and teaching guitar

Interview

Fearlessly challenging the boundaries of community journalism, I'm chatting to Paul Swanson while being hassled round Leamington's Jephson Gardens by the most assertive Jack Russell in Warwickshire. With his indestructible Gibson Blueshawk, Swanner is well respected as the energetic guitar mainspring of the excellent Sam Powell Blues Band. However, today we're talking about his other mission, helping the next generation of local guitar talent to develop their chops through technique, timing and a disciplined approach to practice.

I ask Paul about advice developing guitar players. He thinks about this briefly while I do the responsible dog-owner thing with a little black bag. Then he reminds me that learners are often told, "Here is a set of notes, keep bashing away at them and you will get them". However, as Paul says with a wry grin, recalling part of his own journey as a player,

"I had 10 years of putting CDs on, blasting along with them thinking I sounded like my heroes, and getting absolutely nowhere. If you're doing things in a way that doesn't make you better, you could keep doing that forever and never see any improvement."

This gets me wondering how important it has been for Paul to reflect on his own experiences, both learning and teaching.

"It cuts both ways and I've picked up on a lot of ideas through teaching that I took to my own guitar practice. Using them in my practice cemented down the ideas and showed that they worked for me the same as for my students, the same as the next guy. If it works for everybody then that becomes the foundation for a system, a set of rules you can apply to what turned out to be basically any situation. I've never found a situation I couldn't apply this systematic approach to."

So I ask him just how his teaching style helps students reliably improve their playing without that quiet desperation of directionless bashing. It turns out that the key is systematic and unhurried attention to the mental and physical mechanics that underlie the music.

"Like everything I do on guitar, it's all about reducing music to the nuts and bolts level. I aim to present things in a way that means, if you do it like this you WILL get better".

"Bashing away could mean a million different things to a million different people but it generally means doing it in a fairly unstructured fashion and hoping that you get better as opposed to expecting that you will get better."

Of course, there's a smarter approach that breaks complex musical challenges into units small enough to analyse, learn, ‘debug', and, ultimately, perform with accuracy confidence and feeling.

"I'll approach any problem the same way, which is to isolate the issue, get the student to the stage where they can repeat it correctly and monitor it to make sure they're getting better. If they're not improving, we'll work out why not, attempt to correct it and try again. It's essentially trial and error but with 100% purpose and 100% structure."

A good example here might be separating out technique for the left and right hands.

"One big benefit is in chopping things down so you're only focusing on the left hand or the right hand - divide and conquer I guess. For example, with beginner/intermediates, one major issue can be that they want to watch both hands at the same time. This means they end up playing what I call head tennis, i.e. looking right to see which string they're about to hit with the pick, then looking left to see what the fretting fingers on the left hand are doing, then right again and so on. A good way to avoid that is to simplify things and make one of the hands easy enough that they don't have to look at it. So as part of our investigation we might focus fully on the right hand for a bit by muting out the left hand strings, basically turning the guitar into a crude drum machine where you're only getting clicks from the strings, or we might find a way to simplify the right hand enough that the student can focus purely on what the left hand is doing."

We get talking about the importance of slowing down when learning new skills. What is the right speed to practice a challenging phrase?

"The speed the student can execute it correctly! If that speed means it takes 10 minutes to do 4 notes, that's the speed it needs to be kept to. Of course human nature says, everyone wants to do it faster than they can but the trick is really to remove any concept of musicality from it and view it purely as a technical challenge, can you repeat these movements correctly enough times that things start to stick in the right place in the brain? That's the key to making things easy and I've never found anyone it doesn't work for."

Now the conversation moves on from speed to timing.

"Think of your foot tap as the driving force, certainly in practice and hopefully in performance. Every piece of music has a beat and the foot tap is what I call your ‘rhythm muscle' on display!"

"The challenge is, can you count out loud and tap your foot correctly while playing this piece of music? I'd always been aware that guitar books recommended tapping your foot while you play but they never explained how to get to be able to do it correctly and until ten years ago I'd never thought too much about it. When I began working with students on their foot taps I began spotting major problems with my own and so all the techniques that worked in lessons to improve students' foot taps, I took away and applied to my own practice. I found the same thing for me as for them; if you approached it in a certain manner you would get better at it."

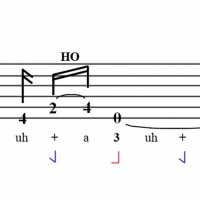

One of Paul's distinctive contributions to guitar tuition is Taplature, a representation of guitar music that combines not only the fingering but also the matching foot movements. There are some strong benefits to including the foot tap. It adds the rhythmic information missing from standard tablature but more importantly, it helps the student feel and learn the groove that makes for a committed and assertive performance.

I suggest that some students may be more talented than others. Perhaps they are better coordinated or have stronger concentration? Or can this systematic approach help any student?

"From my experience, yes. If they humour me by following instructions we can always get someone doing something they couldn't do previously. My experience is that everyone improves at about the same rate, though most think they're the exception to this and that things are harder for them."

At this point I want to know about the difference between a weekend warrior and guys like Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimi Hendrix or Steve Vai.

"Good question! And I'm pretty sure Stevie Ray couldn't answer that. I don't think the guys with the natural talent necessarily understand what they're doing differently. Another big aim of mine with students is to define what that difference is."

"It definitely ties in with the old saying that an amateur practices something till they can do it but a professional practices something till they can't do it wrong. So an amateur is happy just to get through something, well maybe not happy, but that's all they can do and they don't understand how to move to the next level."

"By pulling something apart right down to the bones you can spot problems and say ‘Here's the difference', maybe someone's pull-off isn't quite so clean, they're not hitting a note bang in time because of the physical awkwardness of getting to it - so by defining what you want to improve at you then have a chance to deal with it. There's an actual problem to work on as opposed to, ‘I'll keep doing it and hope to get better."

I ask Paul how students can be sure that they are genuinely making progress.

"There are ways to measure anything on guitar. The big picture measurement is to record yourself, file it, come back to it sometime down the line and record it again. Comparing the two recordings lets you know whether your practice time between the recordings has been put to good use or wasted."

"It's useful to be able to monitor progress on a much smaller scale and I teach students to measure anything and everything they're working on. Getting better at a lick becomes a bit like beating a high score and measuring things means instead of having to hope, we know for sure whether things are improving."

Over a coffee in the excellent Aviary Cafe, I look for some general advice to ensure quality practice. While sneaking a biscuit to the scrounging mutt, Paul recommends three simple principles: 1. Slow down! 2. Break down! 3. Exaggerate!

"Break down is the one that I'd say people overlook the most. i.e. they insist on trying pieces of music that are too big for them to take in with the detail required to get it to the place where it becomes easy, or it means that they overlook too many of the important details so that it never sounds the way they want it to even when they have it learned."

"Slow down is an important one. The point there is, as I've mentioned before, if it takes 10 minutes to play something correctly, that's how slow you need to go. So people think slow is a bit slower than the record speed but it might need to be a fraction of that, and zero miles per hour if necessary."

"Exaggerate means to make things harder in practice than they need to be to just play them. So, when it's time to perform something, it's easy because you've previously pushed it to a higher level in practice. One of my favourite ways to do that is to try playing something at twice your normal volume which forces both hands to work harder."

So, now we've walked off breakfast and reduced the formerly feisty terrier to a cutely snoozy pooch, I ask Paul about opportunities to study with him. He says he is always able to take on keen students either as home visits or via Skype. Lessons are very much adapted to the individual needs of students.

"It's typically, ‘What would you like to work on?' and then find a way of adapting it into my preferred format so as to put in front of them the problems they likely were not aware of but were always blocking their way forward."

"Pulling things apart and digging a whole lot deeper than they had done before."

If you're interested in working with Paul, you can contact him through his website, Old Swanner Guitar Tuition. As a ‘graduate' myself, I can strongly recommend his teaching. He has a unique way of blending a relaxed manner with a disciplined focus on training hands, feet and mind to work together to deliver a clean and confident performance.